More about Thimbles

Magdalena and William Isbister.

Ivory has been fashioned into works of art since Ice Age man carved ivory Mammoth tusks (1). It is not known that thimbles as we know them were used at that time though!

The Romans and Greeks carved ivory statues and jewellery but they did not make thimbles either. Ivory carving was popular in early China and it is thought that the first thimbles as we know them today may have been made in China. The discovery of steel in China led to the production of steel needles (Han Dynasty, 206BC - 202AD) and these in turn resulted in the development of strong needle pushers which were at first cylindrical in shape. It is possible that ivory thimbles were made at this time but none are known to have survived. Although ivory carving was also practiced in other Asian and African countries there are no records of early thimbles.

In Europe a brisk ivory trade was established between ‘Petit Dieppe’ on the West African Coast and Dieppe in France. A flourishing carving tradition was thus established in Dieppe in the 17th century and in the 19th century Dieppe ivory carvers won medals at the ‘Roman Exhibition’ in Rome in 1870.

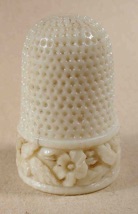

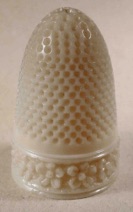

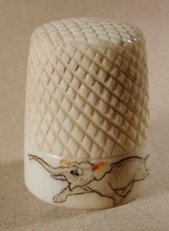

Fig 1 Possibly Dieppe hand carved ivory 19c.

Fig 2 Dieppe hand carved 18c.

The first written mention of an ivory thimble appeared in a Catalan manuscript in about 1365 (2). The first known example of a carved ivory thimble depicts a dog coursing after game, a common theme of the time, from the Renaissance period (2). In 17th century France brass, silver and ivory were listed as the materials from which thimbles were usually made. Elizabeth Barton Stent, a wood and ivory turner, turned ivory thimbles in London in the 1740s (2). Ivory thimbles were advertised as early as 1767 by Charles Shipman, ‘lately from England’ according to his advertising material, of New York (2). It is not known whether the thimbles were actually made in the US or imported from England. Ivory thimbles were being made at this time in England and Germany too. In the late 18th century ivory thimbles were being painted around their bases with polychrome floral motifs in Southern Germany (2). Similar decoration was made in England, but this Lac work originated in India (Fig 3).

Fig 3 Two-Part thimble, painted base, probably English.

Dreesmann (3) shows two ivory thimbles with silver tops from the 18th and 19th centuries, which were discovered in convents in the ‘Low Countries’ where through the 18th and 19th centuries embroidery and sewing were taught.

Increasing prices of ivory in the last century and the development of a substitute, celluloid (Figs 4, Fig 5), caused the cessation of the serious production of ivory thimbles for sewing.

Fig 4 Celluloid 1930. Fig 5 Celluloid finger guard simulating ‘ivory’ 1920.

Some souvenir ivory thimbles are still being made in Asian countries but their sale in the EU is limited by law. Some ivory thimbles come with ‘peeps’ (Fig 10).

Fig 6 Modern, German 1970. Fig 7 Modern ‘ scrimshaw type’ USA 1970.

Fig 8 Modern, New Zealand 1970.

Fig 9 Modern, China 1970. Fig 10 ‘Peep’ ‘’Niagara Falls’’, whale ‘ivory’ 1920.

Ivory represents the dentine of teeth laid down in criss-crossing intersecting layers of slightly different coloured dentine giving rise to the creamy white finely grained material we know as Ivory today. Unlike bone there are no longitudinally running capillaries so the fine black lines or dots/holes seen on section of bone are not seen in ivory. Ivory usually comes from the tusks of elephants or walrus but material from the teeth of the sperm whale or narwhal is sometimes called ‘ivory’.

Fig 11 Modern, walrus ivory USA 2000.

International Conventions have now made it very difficult to move ivory around the world and for example it is an imprisonable offence to import an Ivory thimble into Germany without a certificate from Agricultural authorities confirming that the thimble is in fact ivory and at least 100 years old. Ivory thimbles are rarely found at auction and this in part may reflect the modern regulations controlling the movement of ivory but also because of the rarity of the thimbles themselves. Ivory tends to dry up and become brittle so may easily become damaged – many old thimbles would thus just not have lasted too long and there are very few about now.

It is not possible to identify the country of origin of ivory thimbles with certainty from their shape nor is it possible to date them from either their shape or colour.

Fig 12 Hand painted Indian 1920. Fig 13 Hand painted Indian 1920.

The colour of ivory depends on how it has been handled and kept, and the age of the ivory itself, so that very old ivory may be quite pale and creamy and very new ivory may be quite dark and yellow.

Ivory thimbles may be turned in one piece (Fig 14) and then decorated or they may be made in two parts when the top usually screws onto the body of the thimble (Fig 15, Fig 16).

Fig 14 One-part England 1880. Fig 15 Two-part Indian 1900.

Fig 16 Two-part China 1900.

Some ivory thimbles have a metallic strip around the rim to give greater strength and prevent cracking.

Fig 17 Applied gold rim France 1800. Fig 18 Applied gold rim France 1820.

Fig 19 French with steel band and studs (clouté work - from the French word meaning studded) around base 1820.

Ivory thimbles were particularly popular at the end of the 18th century when ladies spent much of their time making lace and embroidery.

Fig 20 Two-part, India 1850. Fig 21 India 1900.

Fig 22 Hand coloured elephant around base, China 1910.

Smooth topped ivory thimbles were particularly useful for fine silk work, as the silks did not catch on the smooth surface (Figs 23, 24).

Fig 23 Smooth, no indentations, England 1850. Fig 24 Smooth, no indentations, India 1850.

At this same time needlework boxes became popular and were usually made in either India or China (Canton) and imported to Europe (4). The ivory thimbles in the boxes were hand made and because the sizes were not regulated, the thimbles often never fitted their owner and were never used. For this reason many of these thimbles survive today.

Fig 25 Workbox thimble, India 1890. Fig 26 Workbox two-part thimble, India 1890.

Most of the ivory thimbles in collections today were made in the 19th century. Earlier ones seem not to have survived.

It is Important not to confuse real ivory with vegetable ivory, which comes from the Corozo nut. Vegetable ivory was usually used to make thimble holders however and vegetable ivory thimbles themselves are rather rare.

Fig 27 Vegetable ivory, England 1890

Fig 28 Vegetable ivory, steel top, double gold bands and gold studs, South America 1880.

Fig 29 Vegetable ivory Hand engraved flowers signed JFG, USA 1970.

They are still made today in Ecuador as souvenirs (Fig 30)

Fig 30 Vegetable ivory Hand painted flower, Ecuador 1980.

Scrimshaw thimbles seem to have been made of whalebone for the most part by bored whalers in their long evenings when they were not out in their whaling boats. Genuine old thimble scrimshaws seem to be very rare and will not be considered in this paper because they are not really ivory thimbles. Imitations are common (Figs 31, 32).

Fig 31 Modern plastic ‘scrimshaw’ with brass top 1980 (History Craft, Cirencester).

Fig 32 Modern synthetic, possibly French with a petal top and fleur de lis border 1980.

Finally a word of caution. Do not clean ivory thimbles with detergents because the natural oil will be removed. Do not, as stated in one thimble text (5), re oil thimbles with almond oil as the oil may become rancid. It is better to use a fine, light very pure mineral oil which will restore the oils to the ivory and help prevent drying and cracking.

References

1 Lion man of the Hohlenstein Stadel.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lion_man_of_the_Hohlenstein_Stadel

2 Holmes EF. A history of thimbles. London, England: Cornwall Books, 1985. pp. 94.

3 Dreesmann C. A Thimble Full.… Utrecht, Netherlands: Uitgeverij Cambium, 1983. pp. 22.

4 Holmes EF. Thimbles. Dublin, Ireland : Gill and MacMillan, 1976. pp. 53.

5 McConnel B. The story of the thimble. Atglen, USA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1997. pp. 170.

Rund um den Fingerhut 2010; 51: 4

Holmes: ‘Ivory Thimbles’ pp. 94.

Addendum

When the paper about ivory thimbles was first published we are afraid that we knew nothing of Ivory carving and ivory thimble making in Germany. We are grateful to Martti Helsilä for making us aware of our error.

The Odenwald is a low mountain range in Hesse, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg in Germany. Once this area was the centre for ivory carving in Germany, but when the hunting of elephants and the sale of their tusks were prohibited, most of the carving stopped and the shops closed. Two towns in the region were famous for their carving.

Erbach was probably the premiere ivory carving centre in the region and interest in carving dates back to 1769 when Count Franz I of Erbach discovered the exquisite art of ivory carving when he was in Vienna. He returned to Erbach, where wood turning on a lathe was a prosperous industry, and established a guild charter for ivory carvers. Erbach’s recognition as an ivory carving town was delayed until 1873 when at the World’s Fair in Vienna Erbacher ivory carvers unveiled an award winning finely carved ivory rose (the Erbacher Rose). Today the craft of ivory carving is still taught at a local Training College. Although a ban on the ivory trade in 1989 nearly closed down the craft in the town the discovery of large quantities of fossil mammoth tusks and the utilization of vegetable ivory saved Erbach’s ivory carving trade. Nowadays, Erbach is home to ten workshops, and master carvers continue to be taught carving skills at its school.

Michelstadt is the second famous ivory carving town in the Odenwald. It was once a little town of gentlemen farmers but its craftsmen and tradesmen allowed it to grow into a sizeable community with important industrial activities based on the centuries-old iron working crafts. From the cloth weavers’ and dyers’ guild grew a cloth factory and from the foundries grew machine factories. Ivory carving became a starting point for the souvenir industry.

Many of the thimbles made of ivory were souvenir thimbles and would have been little use for sewing; they were more expressions of the carver’s skills (Fig 1)

Fig 1

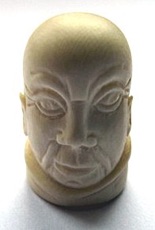

A few thimbles were very plain with painted images (Fig 2).

Fig 2

Some thimbles could have been used for sewing and this thimble is simply made with hand dimpling and an engraved drawing on the side (Fig 3).

Fig 3

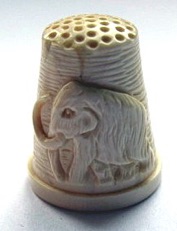

Mammoth tusk thimbles seem to have been less intricately carved and more utilitarian and thus more useful for sewing (Fig 4). There were some which were highly carved though (Fig 5).

Fig 4

Fig 5

We are grateful to Martti Helsilä for allowing us to use his pictures of the Odenwald ivory thimbles in this addendum.

August 2011.

Researched and published in 2002/11

Copyright@2011. All Rights Reserved

Magdalena and William Isbister, Moosbach, Germany

Ivory thimbles

Navigation