More about Thimbles

Magdalena and William Isbister.

Introduction

Holmes (1,2) and Zalkin (3) have written about fake and reproduction thimbles and both Rich and Meacham and Schwall have presented papers on the subject at past Thimble Collectors International (TCI) conventions. Holmes preferred to use the generic term ‘thimble-rigging’ in his writings but we feel that it is clearer not to use a generic term and thus we have used the terms ‘fake’, ‘reproduction, re-issued and ‘equivocal’ in this paper.

Nearly twenty years have passed since Zalkin and Holmes made would be thimble buyers aware of the hazards of buying thimbles in markets and from dealers. The internet with on-line auctions and internet shop selling was not in existence at the time of their writings, thimble collecting was a popular hobby and thimble prices were in general quite high compared to many of the prices today. The incentives for making a fake or copy were thus different and the gains for the would be faker were much higher and thus the spectrum of ‘wrong’ thimbles differed, at this time, from that seen in the present day. Of course these ‘wrong’ thimbles are now probably in collections somewhere but one day will come on the market again. It is thus important for the buyer of today to be aware of the ‘wrong’ thimbles of yesterday and this information is best acquired by reading and discussion with present day experts at meetings and conventions.

At a time when serious thimble collectors seem to be in the decline as evidenced by the abandonment of ‘Thimble and Needlework Tools’ auctions by two major auction houses, the decline in membership numbers of the Dorset thimble Society, the cessation of publication of the Thimble Society of London’s magazine and the publication of several papers in the TCI Bulletin which barely mention a thimble, there continue to be increasing numbers of thimbles offered for sale on on-line auction sites. Although some sites do offer some protection to buyers the sale of the thimble is in reality a ‘buyer beware’ transaction. In this paper we attempt to offer some general advice for would be buyers.

When you buy a thimble it is important to know whether the thimble has been damaged and or repaired or has uncharacteristic features such as added stones or atypical stone tops (4). If evidence of these problems exists then alarm bells should start to ring and you should consider your bid/purchase very carefully. It may be quite reasonable to buy a rare damaged thimble, but the seller should acknowledge that the damage exists. If the seller does not make such an admission then you should tread warily – there may be other problems with the thimble too because in this instance the seller is selling to deceive – ignorance is no excuse!

The main problem of buying on line is that you do not have the opportunity to handle the thimble and examine it in detail – you have to rely on the seller’s pictures. Often a thimble will feel ‘wrong’ when it may look pretty good! It may be too thick, too heavy, too rough or too light and you cannot get this information from a picture. The best advice that we can give is to know how the thimble should look and feel (see and handle as many thimbles as possible at sales malls and conventions) and then buy from a reputable seller.

Clearly it is impossible to show every newly made reproduction thimble, every fake and every misleading description that has been on the web but we will attempt to show and describe examples from each category. Further illustrations may be seen on the excellent Thimble Collectors International web site (http://thimblecollectors.com/) but membership of TCI is necessary in order to view the page.

Fake thimbles

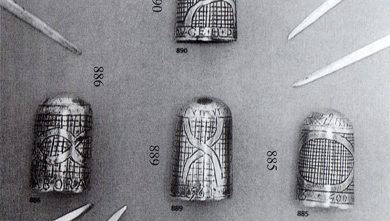

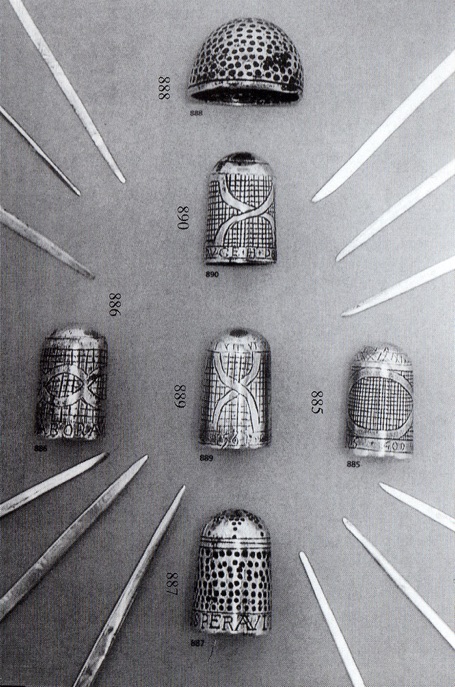

A fake thimble is a thimble made to appear otherwise than it actually is. Fake thimbles are thus made to deliberately deceive for profit. Fake thimbles are made to trick the buyer into thinking that the thimble is a rare and difficult to find one and this results in an inappropriately high price being paid resulting in a big profit for the seller. A good example of this would be the silver thimbles which were sold at a recent auction and which were claimed to be made in England in the 16th and 17th centuries (fig 1). They realised between 1600 –3500 pounds each but when their authenticity was questioned by some knowledgeable collectors and metallurgical tests were subsequently performed, the auction house offered to give the buyers their money back!

Fig 1

It appeared that the silver content was not consistent with the apparent age, the implication being that they had been made from silver melted down from later pieces (personal communication, Robert Bleasdale). Although these thimbles did have strap work decoration, the engraving seemed to be ‘scratched’ and very superficial in comparison with genuine thimbles of the same age (fig 2, 3).

Fig 2 Fig 3

Sixteenth century silver thimbles (fig 2) were usually shorter and more simply decorated than 17th century silver thimbles (fig 3).

Making a plausible fake is time consuming and costly and in order for the process to be profitable there must be a guaranteed market for the finished product. It follows that it is not worth bothering to ‘fake’ an inexpensive thimble if the return is likely to be low although some inexpensive American thimbles have been ‘faked’. For these reasons there actually seem to be relatively few fake thimbles being made at the present time. Reproductions, re-issues and thimbles that are misrepresented are not fakes but are much more frequently seen now.

In addition to the 17th century English silver fakes mentioned above we have only been aware of faked Fabergé and Russian enamel thimbles.

Fabergé

The Fabergé workshops made very few thimbles (5), Fabergé items seem to make high prices at auction and therefore it could be profitable to fake a Fabergé thimble. These thimbles may be known as Fauxbergé and we are aware of at least one example.

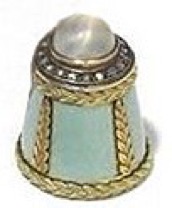

Fig 4 Fig 5

The Fabergé thimble on the left (fig 4) is an original Fabergé thimble. The workmaster is said to be Henrik Wigström. The other thimble is a rather more crudely made ‘copy’ with ‘apocryphal Russian’ marks inside the top (fig 5).

We have seen another silver thimble (fig 6) that was not sold at a high price but it did have a Fabergé mark (fig 7) in addition to the German 800 mark for silver purity and a pre-revolution Russian import mark (fig 8). The thimble was made in Germany and probably exported to Russia but how and why the Fabergé mark came to be stamped on the thimble remains a mystery. Original Fabergé punches seem to have been ‘removed’ to the West during the communist times and now are freely used by fake thimble makers. The punch marks may thus be ‘original’ but the thimbles are most certainly not.

Fig 6 Fig 7 Fig 8

Russian Enamel

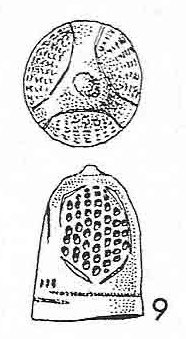

No enamel, filigree, Fabergé thimble has ever been described to our knowledge, but some such thimbles have been found with what could be mistaken as Fabergé workmasters marks (fig 9). In these cases there is usually another mistake in the marking or the position of the mark and we have never seen a seller actually claim that these thimbles were Fabergé thimbles. The mistake is left to the buyer to make and if he or she is tempted the seller cannot be blamed!

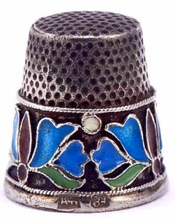

Fig 9 Fig 10

One such thimble was ‘cast’ and then enamelled. The enamel work is good and the marks inside the top are all correct for the supposed age and place of manufacture of the thimble (fig 9). The workmasters mark, AT, could belong to Alfred Thielemann (fig 10), a Fabergé workmaster, who worked in St Petersburg. He is not known to have made cloisonné, shaded or champlevé enamel. The town mark is for Moscow (George and the Dragon) and since Alfred Thielemann did not work in Moscow his mark would never have been associated with a Moscow mark. Russian filigree enamel thimbles were usually marked on the rim and thus the positioning of the mark is not correct for the type of thimble. The thimble was never made by a Fabergé workmaster far less Alfred Thielemann but this was never the claim of the seller!

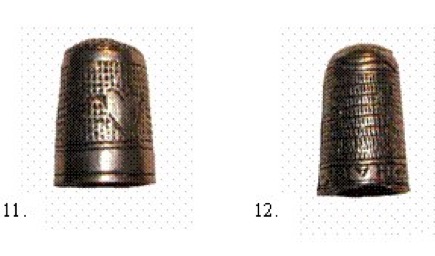

In general cast thimbles are cruder, thicker and heavier than the original thimble that they have been copied from. This even applies to thimbles that copy cast originals (fig 72). The inside is often rough although some may be cleaned and turned on a lathe to produce a smooth appearance (fig 10). Often the ‘seam’ of the mould will leave a mark on the outside of the thimble (fig 11).

Russian enamel filigree thimbles were all made by applying filigree wire to the surface of a thimble and then the enamel was placed within the filigree compartments of the pattern before baking. Every new colour required a new baking. This method of manufacture applies to old and new Russian filigree enamel thimbles although, the later the time of manufacture, the cruder the workmanship became. Filigree thimbles were not cast and thus if you see a ‘filigree’ thimble with a clear casting mark (fig 11, 13) then clearly the thimble is a fake. In some of these thimbles the ‘enamel’ may simply be paint or nail polish. If such a thimble has a Fabergé workmaster’s mark in addition (Ф.P. for Fedor Rückert) then this thimble was definitely made to deceive (fig 12). Incidentally Rückert was not known to have ever made a thimble. Many thimbles of this type appeared on the market at the end of the eighties and early nineties as the border between East and West was breaking down. One such thimble was offered in a major thimble auction as an ‘early twentieth-century’, Russian silver-gilt and enamel thimble. The estimated price was 250-300 pounds but the thimble was not sold!

Fig 11 Fig 12

Fig 13

In comparison with the genuine pre-revolution Russian enamel thimbles, the ’fakes’ seem to be of limited design (possibly only five patterns), often have obvious casting marks (fig 11), and have flat tops (fig 13).

Fig 14 Fig 15

Genuine pre-revolution filigree thimbles (fig 14) tended to be taller than later models, were deep drawn and often had turnover rims. It is important to remember that Russian filigree thimbles are still being made today. These are neither fakes nor reproductions they are simply rather less well made modern Russian enamel filigree thimbles (fig 15). The second silver gilt thimble (fig 15) was actually cast and made in the fifties and bears the star with hammer and sickle mark.

Russian Niello thimbles

There has been a lot of discussion regarding whether some niello and engraved thimbles from the Caucasus were actually thimbles or cartridge case caps. Some of these ‘thimbles’ have smooth tops and sides and would be pretty unsuitable for needle pushing (fig 16). They must be cartridge case tops. Others have a smooth flat protrusion at the top and they too are pretty unlikely to be thimbles (fig 17). We have seen some, however, that are squat and have roughened areas between the niello decoration and these we feel might be actually made as thimbles (fig 18). We have been told by a lady from the Caucasus that, whatever the original intention of the object, many were, in fact, used as thimbles by Caucasian women in the last century.

Fig 16 Fig 17

Fig 18

Others

An unknown maker is responsible for this very strange thimble (fig 19). It is made in two parts with a plain dimpled top, a plain border decorated with daisies and a plain flat rim. The method of construction and the 925 mark suggest a continental origin with earlier English marks added later. Interestingly all of the added marks (heavy stamp against a back plate) match with regard to date and maker - Nathaniel Mills (1850) who used the Birmingham assay office in the 19C (925 - D.P - N.M - G, anchor, lion, Queens bust).

Fig 19

Reproduction thimbles

A reproduction thimble is a duplicate or copy of an original thimble. It is not a thimble that resembles the design of another thimble that is simply a variant, and which may be made, in fact, by a different maker all together. A replica is an exact copy of an original but often the term is used synonymously with reproduction. Sometimes a thimble is so rare that it becomes unlikely that you will ever find an original for your collection. You may still, however, wish to have a copy of the rare thimble and in this case it is perfectly reasonable to buy a reproduction. There is only a problem when a seller tries to sell you a reproduction as a genuine original. You can avoid this trap, at least in part, by having some idea of the common reproduction thimbles that have been on the market in recent times.

Cast from The Past, UK.

Cast from The Past is a long established casting company that specialises in the reproduction of historic costume decoration and fastenings including a few thimbles. Castings are made in pewter and then ‘antiqued’.

Fig 20

According to the brochure article (fig 20) number ’11’ is a reproduction of a Tudor thimble that was originally cast in silver and was a ‘rare’ 16th century thimble. Engraved around the base of the original thimble was ‘my hart is yours’. Article number ‘12’ bears two hearts and on the band below them is a single word ‘ME’. Clearly the numbers have been transposed in the brochure.

Cast from the past no longer exists

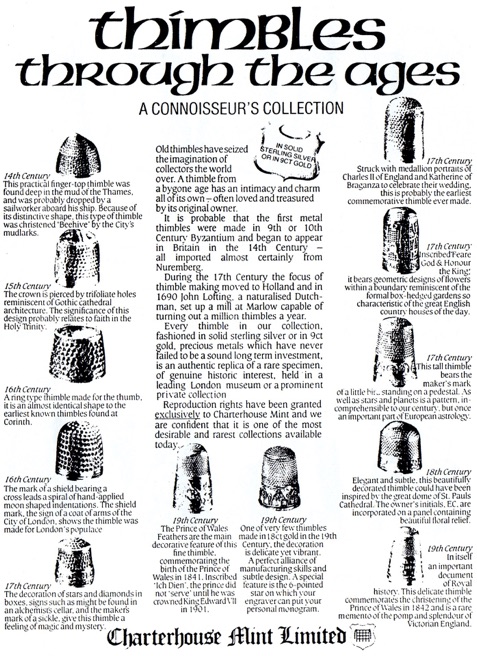

Charterhouse Mint, London

In the mid-eighties the Charterhouse Mint produced a series of silver thimble reproductions (fig 21). The original thimbles were held in either museums or private collections and the Charterhouse Mint was granted sole reproduction rights as explained in their advertisement. All thimbles were assayed in London, hallmarked and stamped with the maker’s mark CM (fig 22, 23, 24).

Fig 21

Fig 22 Fig 23

Fig 24

The Charterhouse Mint no longer exists.

Bertus van Dikkenberg, Veenendaal, The Netherlands

Bertus van Dikkenberg has a thimble museum in Veenendaal and several thimbles have been identified with a Dutch mark which has been attributed to Bertus van Dikkenberg. Whether he actually copied the original thimbles or simply added his own ‘mark’ to the thimbles in question is difficult to say. There do not appear to be any of the original marks on the copied thimbles and since Bertus van Dikkenberg does not seem to be a silversmith it is difficult to see how he could have manufactured the thimbles with his ‘mark’ himself.

Fig 25 Fig 26

A British thimble with a Vandyked rim (fig 25) has Dutch marks for purity (lion), the assay office (helmeted figure and letter) and a date letter on the band. The ‘maker’s mark’ is on the left but is not readable (fig 26).

Fig 27

Lucern Wulf, a silversmith from Arizona, originally made this thimble (fig 27) but it has subsequently appeared without the Wulf mark (LW or ‘Lucerne’) but with a mark similar to the mark on the English thimble above (fig 26).

Stephen Frost, Warwick Models, England

Warwick Thimbles was established in 1981 by Stephen Frost. Frost designed thimbles were cast in pewter, and hand painted if appropriate. Warwick thimbles are known to have made a pewter reproduction of the Deakin and Francis 1897 thimble commemorating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria (fig 28). The reproduction thimble has a hole in the rim to signify that it is a reproduction (fig 29).

Fig 28 Fig 29

Warwick thimbles also made a pewter reproduction of a silver thimble made to commemorate the Exhibition of all Nations (fig 30) held in 1851 (6).

Fig 30

http://www.warwickthimbles.com/

Heirloom Editions Ltd

Heirloom Editions Ltd was started in 1978 by Barbara Ringer (personal communication, Barbara Ringer). They manufactured and imported thimbles for collectors. In December 2004 they moved from California to Georgia. Heirloom Editions Ltd created their own porcelain shapes and cast porcelain bisque thimbles for their many artists to paint. They also cast pewter, gold, sterling silver and bronze thimbles. The thimbles were sold in ‘Treasure Chest’ boxes. Heirloom Editions Ltd no longer produce cast replica thimbles.

Fig 31

Fig 32

Fig 33

A cast Spanish replica (fig 31) and the accompanying label, together with two replica ‘Roman’ thimbles (fig 32) and their label and a replica of a ‘Persian’ thimble and the label which accompanied it (fig 33) were amongst some of the replica thimbles and labels produced by this company in the eighties.

The cast Hispano-Moresque replica (fig 31) was correctly identified by Heirloom Editions Ltd but the two ‘Roman’ thimbles were not. The left ‘Roman’ thimble was, in fact, a replica of a thimble found in Hama, Syria (fig 34, 35). The other two thimbles were copied from thimbles made in Nürnberg in Medieval times.

Fig 34 Fig 35

In the early thirties a Danish archaeological excavation was undertaken at Hama, Syria (7) and several thimbles were found. One had been previously identified as a Corinthian thimble but of the remaining thimbles, two, of similar design, had never been identified before (fig 34,35). For this reason they came to be known as Hama thimbles. They are very rare but seem to have been reproduced by at least two makers.

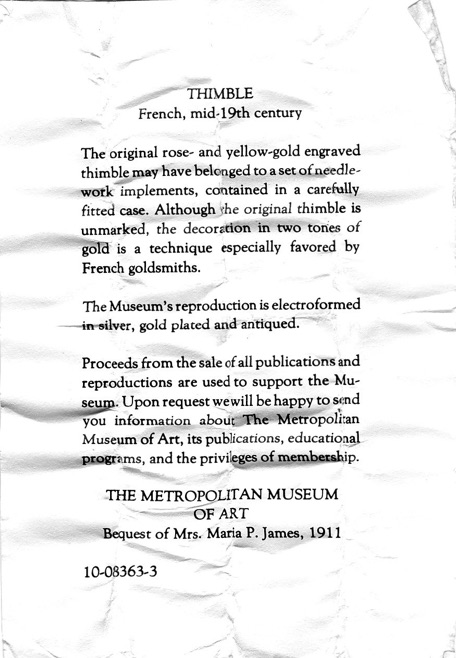

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

In the eighties the Metropolitan Museum of Art made a gilded brass reproduction of an 19c French tall thimble (fig 36, 37). The original thimble is in the museum collection and was donated by Mrs. Maria P. James in 1911. The reproduction was clearly marked MMA (fig 37). A French two colour gold thimble from the 18th century is shown for comparison (fig 38).

Fig 36

Fig 37 Fig 38

Mary Rose Trading Company, Portsmouth.

Fig 39

The Mary Rose was one of King Henry Vlll’s favourite ships (fig 39). It sunk in the Solent in 1545. The ship was found in 1971 and salvaged in 1982. The Mary Rose Trading Company (fig 40), to commemorate the raising of the Tudor warship, produced a brass replica of one of the 13 copper alloy thimbles found onboard the ship (fig 41). The thimble may have been cast by Stephen Frost.

Fig 40

Fig 41

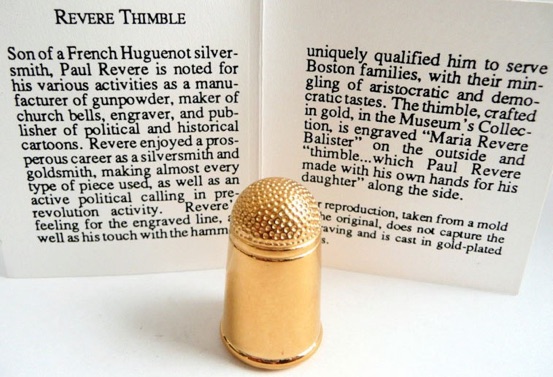

Museum of Fine Art, Boston, MA.

The Museum of Fine Art in Boston made a gold reproduction of the thimble that was supposed to have been made for his own daughter by Paul Revere in 1805 (fig 42).

Fig 42

It is much heavier than the MMA reproduction.

New England Pewter Co.

Founded in 1974, the New England Pewter Co. make pewter items to order. In the mid eighties they made a reproduction ‘French’ thimble depicting a griffin and a serpent, which were made to look ‘applied’ (fig 43). The border was stamped with what was supposed to be a Louis Lenain maker’s mark and a Boars head.

Fig 43

New England Pewter will still make thimbles to order.

http://www.newenglandpewter.com/

Ludwig Redl

In 1984 Ludwig Redl, an Austrian sculptor, who worked in Vienna, London and the USA, made a series of thimbles depicting scenes from Shakespeare. This thimble is probably a later reissue (fig 44, 45). It has a London assay mark for 1992 and an unknown maker’s mark – GJD.

Fig 44 Fig 45

GJ van den Berg Jr, Schoonhoven

In 1990 a Dutch silversmith, GJ van den Berg Jr, made a copy of a 16th century Dutch thimble, now in Zeeuws Museum, Middleburg, commemorating the marriage of Sara Reigersberg in 1594. The thimble (fig 46), as the original, was made of cast silver in two parts. The outer part has two entwined hands on it's top, symbolising marriage. The inner thimble (fig 47) is engraved with four allegorical scenes depicting hope, charity, justice and fidelity. (spes, caritas, iustitia, fides in Latin, as engraved on the thimble). The text around the border reads: 'Sara Reigersberg 1594'. The thimble has gilded highlights and is marked with GB5 (GJ van den Berg Jr), a lion ll (.835 purity), a Minerva head (duty paid) and N (1999).

Fig 46 Fig 47

Thimbles Only, USA - Gimbels and Sons, New York.

Thimbles Only made a brass thimble with what was supposed to be an ‘applied’ ‘campaign button’ which stated "Long live the president - GW”. The reproduction thimble (fig 48) was originally sold in the eighties in America for 10 - 15$! It was made from a casting of the original campaign badge which itself was made in silver and possibly made by Paul Revere. Recently one such thimble was listed on Ebay as a ‘Rare 1789 George Washington Inaugural thimble’ with a starting price of $US 1999.99! Several other similar thimbles have been on Ebay in recent times.

Fig 48

Thimbles Only no longer seem to be in existence.

Sok Ung

Fig 49

Sok Ung, a Cambodian-American silversmith created a ‘replica’ series based on some thimbles in the von Hoelle collection (8). The thimbles were cast in silver and may be identified by finding the maker’s mark SU in the top (fig 49).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Irene Schwall for permission to reproduce some of her images and Wolf-Dieter Scholz for help in identifying some of the thimble makers.

References

-

1.Holmes EF. A history of thimbles. London: Cornwall Books, 1985. pp. 220

-

2.Holmes EF. Thimble-RiggingThimble. Notes and Queries 1992; 15: 7.

-

3.Zalkin E. Zalkin’s Handbook of Thimbles & Sewing Implements, 1st ed. Willow Grove: Warman Publishing Co., Inc., 1985. pp. 243

-

4.Isbister M, Isbister W. Hybrid Thimbles. TCI Bulletin 2009; Winter: 1

-

5.Isbister M, Isbister W. Fabergé Thimbles. TCI Bulletin 2009; Summer: 1

-

6.Isbister M, Isbister W. Exposition Thimbles. TCI Bulletin 2010; Summer: 1

-

7.Plough G, et al. Hama, Fouilles et Recherches 1931- 1938 lV3. Copenhagen: Fondation Carlsberg, 1969. pp. 86.

-

8.von Hoelle JJ. Thimble collector’s encyclopedia. Illinois: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1986. pp. 134.

Holmes: ‘Thimble Rigging’ pp. 220.

Researched and published in 2002/11

Copyright@2011. All Rights Reserved

Magdalena and William Isbister, Moosbach, Germany

about ‘fakes’, reproductions and re-issues i

Navigation